The Colonial Counter- revolution in france

From de Gaulle to Sarkozy

By Sadri Khiari

Translated by Ames Hodges

We see the hatred we elicit, Islamophobia, Negrophobia; we see police numbers increase, repression spread, mechanisms of control and surveillance strengthened, structures of corruption and cronyism flourish, and bodies of institutionalization, integration, and supervision develop, but we do not see the cause, or one of the causes, which is none other than the threat that we now pose to the white order.—from The Colonial Counter-Revolution

Just as capital produced classes and patriarchy produced genders, colonialism produced race. In The Colonial Counter-Revolution, Sadri Khiari outlines how and when American-style slavery created the racial system, not just in the United States but internationally, and why the development of relationships of equality within the white community favored the crystallization of specifically racial social relations. More than just a response to the dialogue, debate, and trauma of immigration today, this book looks beyond the right/left dichotomy of the issue in politics to the more fundamental political existence of immigrants and Blacks, who must exist politically if they are to exist whatsoever. Race is not biological: race is political. And it is the manifestation of the colonial counter-revolution. In France, that counter-revolution started with General de Gaulle, and continues today, where the anti-colonialist fight of Palestinian Arabs and the anti-racist fight of Arabs and Blacks in France have the same adversary: white Western domination.

Can The Monster Speak

November 2019, Paul Preciado was invited to speak in front of 3,500 psychoanalysts at the École de la Cause Freudienne's annual conference in Paris. Standing in front of the profession for whom he is a “mentally ill person” suffering from “gender dysphoria,” Preciado draws inspiration in his lecture from Kafka's “Report to an Academy,” in which a monkey tells an assembly of scientists that human subjectivity is a cage comparable to one made of metal bars.

Speaking from his own “mutant” cage, Preciado does not so much criticize the homophobia and transphobia of the founders of psychoanalysis as demonstrate the discipline's complicity with the ideology of sexual difference dating back to the colonial era—an ideology which is today rendered obsolete by technological advances allowing us to alter our bodies and procreate differently. Preciado calls for a radical transformation of psychological and psychoanalytic discourse and practices, arguing for a new epistemology capable of allowing for a multiplicity of living bodies without reducing the body to its sole heterosexual reproductive capability, and without legitimizing hetero-patriarchal and colonial violence.

Causing a veritable outcry among the assembly, Preciado was heckled and booed and unable to finish. The lecture, filmed on smartphones, was published online, where fragments were transcribed, translated ,and published with no regard for exactitude. With this volume, Can the Monster Speak? is published in a definitive translation for the first time.

The Letters of Mina harker

By Dodie Bellamy

Introduction by Emily Gould

Hypocrisy's not the problem, I think, it's allegory the breeding ground of paranoia. The act of reading into—how does one know when to stop? KK says that Dodie has the advantage because she's physical and I'm “only psychic.” … The truth is: everyone is adopted. My true mother wore a turtleneck and a long braid down her back, drove a Karmann Ghia, drank Chianti in dark corners, fucked Gregroy Corso …—Dodie Bellamy, The Letters of Mina Harker

First published in 1998, Dodie Bellamy's debut novel The Letters of Mina Harkersought to resuscitate this minor character from Bram Stoker's Dracula and reimagine her as an independent woman living in San Francisco during the 1980s—a woman not unlike Dodie Bellamy. Harker confesses the most intimate details of her relationships with four different men in a series of letters. Vampirizing Mina Harker, Bellamy turns the novel into a laboratory: a series of attempted transmutations between the two women in which the real story occurs in the gaps and the slippages. Lampooning the intellectual theory-speak of that era, Bellamy's narrator fights to inhabit her own sexuality despite feelings of vulnerability and destruction. Stylish but ruthlessly unpretentious, The Letters of Mina Harker was Bellamy's first major claim to the literary space she would come to inhabit.

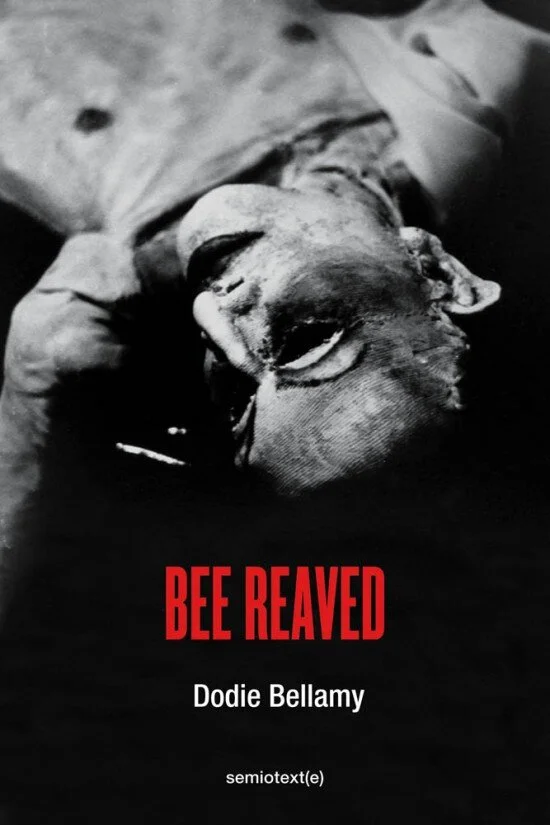

Bee Reaved

By Dodie Bellamy

So. Much. Information. When does one expand? Cut back? Stop researching? When is enough enough? Like Colette's aging courtesan Lea in the Chéri books, I straddle two centuries that are drifting further and further apart.—Dodie Bellamy, “Hoarding as Ecriture”

This new collection of essays, selected by Dodie Bellamy after the death of Kevin Killian, her companion and husband of thirty-three years, circles around loss and abandonment large and small. Bellamy's highly focused selection comprises pieces written over three decades, in which the themes consistent within her work emerge with new force and clarity: disenfranchisement, vulgarity, American working class life, aesthetic values, profound embarrassment. Bellamy writes with shocking, and often hilarious, candor about the experience of turning her literary archive over to the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale and about being targeted by an enraged online anti-capitalist stalker. Just as she did in her previous essay collection, When the Sick Rule the World, Bellamy examines aspects of contemporary life with deep intelligence, intimacy, ambivalence, and calm.

The Man Who Saw Through Himself

How Michel Leiris changed autobiography.

By Sasha Frere-Jones

this article appeared in The New Yorker and the original can be found here

December 9, 2020

When Michel Leiris died, in 1990, at the age of eighty-nine, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote, in Libération, that Leiris was “indisputably one of the great writers of the century.” That would seem to be a big claim, especially if the name Leiris meant nothing to you. What was so great about him? The anthropologist Aleksandar Bošković wrote, in 2003, that “there is perhaps no single figure that influenced so strongly French ethnology and anthropology.” This is one Leiris. But, Bošković wrote, Leiris was also an “artist, poet, writer, critic, traveller, surrealist . . . a true ‘Renaissance Man’ whose friends included Breton, Bataille, Giacometti, Picasso, Césaire, and Métraux.” This gets us closer.

Leiris was, before anything, a tireless witness to lived experience. The term he preferred for most of his work was not “memoir” but “autobiographical essay,” and he applied the rigor of an objective observer to his recording of the subjective. Born in 1901, he worked steadily for seven decades, but his books have yet to secure a spot with most Anglophone readers. At least five of the translated Leiris volumes are indispensable. These include two recent English editions, whose late appearance helps explain the low profile: the 2019 Semiotext(e) edition of “The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat,” which was first published in 1981, and “Phantom Africa,” published by Seagull Books, in 2019, eighty-five years after it was released in French. “The Rules of the Game,” an autobiography published in four volumes, between 1948 and 1976, is Leiris’s longest and most essential work, glacially slow and furiously alive. I can’t vouch for the fourth and final book, “Frêle Bruit,” because it hasn’t yet appeared in English, but the first three volumes—“Scratches,” “Scraps,” and “Fibrils,” as translated by Lydia Davis—are among the most astonishing books I’ve read.

Leiris was a shy and flinty nonbeliever, who valued exactitude above all and who wrote nested, page-long sentences to create “a series of screens” between himself and his ideas. He escaped calcification by holding fast to his curiosity and built ethical strength by observing the slow boil of his consciousness. By the nineteen-fifties, he was firmly anti-colonialist, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist. In 1976, when he was seventy-four, he wrote that his core themes were “an aspiration to the marvellous, a desire to commit himself to the struggle against the flagrant injustices of society, a desire for universalism which has led him to have direct contacts with cultures other than his own.” In 2020, he was a delightful companion.

Leiris stumbled onto his themes. As a university student, he flirted with jazz and chemistry, before graduating with a degree in philosophy. He spent the next few years working in Paris, and by 1929 he had married, gained renown as a poet, and joined then broken with the Surrealist movement. (He remained committed to the “broadly defined psychological and social liberation” that Surrealism espoused.) That year, he became an editor for Georges Bataille’s Documents, a heterodox magazine that served as a workshop for writers floating through and away from the Surrealist epicenter. According to one front cover, the magazine was dedicated to “doctrines, archaeology, fine arts, and ethnography.” Ethnography was then a barely defined field in France, but its promise caught Leiris’s attention. Eager to get out of Europe, he agreed, in 1931, to be the “secretary-archivist” for a two-year expedition, organized by the anthropologist Marcel Griaule, across sub-Saharan Africa.

Leiris’s account of that trip, “Phantom Africa,” would be his first great work. Leiris did not approach what he called the “fortuitous circumstance” of his journey as a traditional ethnographer, partly because he had no training in the field. Instead, he kept a diary and—according to Brent Hayes Edwards, who translated the new edition—“was adamant that, aside from minor corrections,” the entries “were not revised after the fact.” The result is more than six hundred pages of journal entries, which recount dreams, the behavior of soldiers, a variety of conflicts with Griaule, erotic projections, aches, other aches, and a running measure of his distance from both the people he was studying and the people who had sent him to do the studying. (The first English translation, by Robin Chancellor, was abandoned after the book’s publisher demanded extensive cuts to what he called “schoolboys’ lavatory wall dirt.” Leiris did not agree to the cuts.) On the trip, Leiris used file cards to document the items his group would take to France. For the rest of his life, he would use the same method to organize ideas for his books.

Leiris wrote that “Phantom Africa” was the aggregate of “what would result when I forced myself to record virtually everything that happened around me and everything that went through my head.” One can sense the autobiographer taking shape in these lines, but Leiris also found room, in his mind, to make an argument about ethnography. “Phantom Africa” confounded the field’s claims to objectivity by pointing out that the ethnographer is often just recording himself. There was a challenge, too, in the book’s explicit political critique. In his entries, Leiris questioned the validity of the French colonial mind-set and, more specifically, the moral implications of collecting so much butin (booty) for French museums. (Some of the butin that Leiris described is now being considered by Emmanuel Macron for restitution.) After the book came out, in 1934, Griaule and Leiris had a falling out. Five years later, in an unsent letter written to Bataille, Leiris was still warning against the “imposition of our European casts of mind upon the facts” of ethnography. “However intensely we imagined living the experience of the native person,” he wrote, “we cannot enter his skin, and it is always our own experience that we live.”

Most Americans first encountered a Leiris who had little to do with ethnography. In 1939, Leiris published “Manhood,” a memoir that he’d begun writing before his trip with Griaule. More than two decades later, Susan Sontag reviewed Richard Howard’s English translation for The New York Review of Books. Her oft-quoted opening is “Plunked down in translation in the year 1963, Michel Leiris’s brilliant and repulsive autobiographical narrative L’Age d’Homme, is at first rather puzzling.” (The essay became the foreword for a later edition of the book, the word “repulsive” subtracted.) Sontag reads Leiris’s honesty as “an especially powerful instance of the venerable preoccupation with sincerity peculiar to French letters.” This interpretation leads to mention of Montaigne, a common move in Leiris criticism, though Montaigne was generally more concerned with coming off well. Not so Leiris, who opens “Manhood” with a slow, disgusted X-ray of himself. “I loathe unexpectedly catching sight of myself in a mirror, for unless I have prepared myself for the confrontation, I seem humiliatingly ugly to myself each time,” he writes.

For Leiris, even self-esteem is suspect, another trap between you and experience. In 1946, in an afterword to “Manhood,” Leiris wrote that the book was “the negation of a novel.” “In it,” he wrote, “I set out mainly to condense, almost in the rough, an ensemble of images and facts that I refused to exploit by allowing my imagination to work on them.” Even if Sontag’s response was partly disparaging—“The book has no movement or direction,” she wrote, and “provides no consummation or climax”—she did see Leiris’s broader project clearly. “Manhood is another of those very modern books which are fully intelligible only as part of the project of a life,” she wrote. “A book,” in other words, “is an action, giving on to other actions.”

“Manhood” was absolutely part of that project, but it may not have been the most felicitous way to introduce Anglophone readers to Leiris. The “impassioned frankness” that Leiris longed for is muddled by an atypical focus on the narcissistic injuries of his early years. But there was more to come. In his mid-thirties, Leiris began the decades-long autobiographical study that became “The Rules of the Game.” The first volume, “Scratches,” appeared in 1948. Like “Manhood,” the book was an “action,” but Leiris seemed to have changed his relationship to language. According to Davis’s introduction, Leiris said that he could “scarcely see the literary use of speech as anything but a means of sharpening one’s consciousness in order to be more—and in a better way—alive.” His sentences had blossomed into a new variant, which held the reader close and pushed time into the background. Leiris had found the music of his consciousness, and it obeyed a slow, searching tempo.

“Scratches” begins with Leiris’s earliest memories, of carpet patterns and lead soldiers and alphabet books. He pairs the associative logic of Documents with the mode of Proust and, affixing one idea to another and another, lets both run to the pulse of memory. This accretive pace, a ball of gum rolling through the senses, means that his memory of his father’s phonograph begins with the word “Persephone” and takes dozens of pages to unfold. “Persephone” leads to “gramophone” and then to “diaphragm,” which leads to an examination of the “slightly fatty quality” of the surface noise heard when the grooves of a wax cylinder are traced by a needle and amplified through a metal horn, creating a “tempest in a teapot (or even in a cup for mixing watercolors), a seismic tremor racking the thickness of a crystal lens.” Davis, who translated much of “The Rules of the Game,” told me that she “delighted in reconstructing the complex syntax” of such sentences, and that “Leiris’s style is, if anything, even more convoluted or complex than Proust’s.” Davis has described both Leiris and Proust as using a “hypotactic structure,” with many subordinate clauses, and the poet Jean Laude called Leiris’s method “fugal,” in conversation with itself. These are accurate summations, but it remains hard to capture, in a comprehensive way, what was a new mode for Leiris, a long and loose cadence that allowed his writing to embody his thinking.

In 1981, five years after “Frêle Bruit,” the final volume of “The Rules of the Game,” came out, Leiris published “The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat,” which has been newly translated by Christine Pichini. Less a coda to his masterwork than its continuation, “The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat” is perhaps the best introduction to Leiris, his interests, and the curve of his rhythms. If skepticism is central to his project, you see it here, at the level of the sentence, where his subordinate clauses delay and delay, pushing the point away from you as you read.

This book is a memoir, again, with an oddly specific orientation. One axis is a series of twenty-five observations about Édouard Manet’s painting “Olympia,” which features a nude white woman, her neck ringed with black ribbon, being brought flowers by a clothed Black servant. Leiris doesn’t interpret the painting so much as study himself in its presence. The other axis is a chain of observations, each a digression from the last, about Leiris’s neighborhood. Two young women in a sports car are trying to pick him up (he hopes), a beggar argues with him, and the trees near his house are “so high, so straight and so close together that inside them not a sound is heard, as if they had placed sound outside of our reach while soaring—fearless—towards the sky and pushing sound up, out of the compact mass of the highest branches, towards a space of quarantine.”

“Olympia” is the ribbon that ties the book together. Leiris’s father told the writer that Manet had painted a “lifeless figure whose formal stiffness was as repellent as her almost cadaverous complexion.” Leiris disagreed. He believed that the “ribbon and other accessories only emphasize her nudity,” and that the ribbon itself is “the unnecessary detail that hooks us and makes Olympia real.” This fetishistic attention is the central subject of the book. For Leiris, the ribbon is “the rope that keeps me from foundering.” He keeps looking for ways to connect events to totems, “a detail to use as a lever, like the ribbon.”

Because the crucial detail could lie anywhere, waiting to be uncovered, Leiris tends not to weight his experiences differently. Each event is presented as equally animated or blank, and the smallest experiences are some of the richest. “While smoking a cigarette and drinking tea in my bedroom in Paris, the desire often strikes me—irrational but acutely felt—to smoke a cigarette,” Leiris writes. “But I am already smoking, and thus it is absurd to wish to do something that, quite simply, I’m in the middle of doing.” At one point, Leiris argues with himself for seven pages about how to describe and interpret sunlight in the Black Forest: “Limpid patches somehow transforming the terrestrial landscape into a kind of negative of the celestial landscape, which itself was stained by fat, dark clouds.” Eventually, after ruminating on writing, death, and opera, he turns the lens back to himself, claiming to be a failure—“the preoccupied snob and unquiet man I have always been”—just as he succeeds. “While we’re in the thick of it, we would like the book, a tossed pebble, to make some waves,” he writes. “But, whatever acclaim it may receive, the party will already be over, the spell already broken.”

In “Scratches,” Leiris wrote that he felt an “irrational repugnance at the idea of going straight to the point.” Several decades later, in 1987, three years before his death and after all of his books had been written, he said that “a person in our day and age who has self-respect owes it to himself to be as lucid as he can possibly be.” These ideas, seemingly at odds, are, in fact, two sides of the same belief—that language, properly engaged, can reveal the holy glint of experience. For Leiris, it could also provide something like an ethics. He loved the sounds of words, their accidental commonalities, the fellowship found within a family of writers, and the house of the sentence itself, which, if built properly, contains both what has happened to us and how we’ve perceived it, at the exact same time, again and again.

CONVERSATIONS the pleasure principle: Stephanie LaCava

Bernadette Van-Huy, Picnoleptic, 2018. Courtesy: the artist

This article originally appeared in Mousse Magazine, the original article can be found here

CONVERSATIONS

the pleasure principle: Stephanie LaCava

Estelle Hoy in Conversation with Stephanie LaCava

Hot Pre-Raphaelite waifs in sharp-witted pas de deux sink low into art world tropes and clichés in Stephanie LaCava’s clever new book The Superrationals (Semiotext(e), 2020): an enigmatic jeune fille in a motel bathtub flicking her Cosey Fanni Tutti; big-shot collectors from uptown New York or downtown Paris; Dada-inspired mood boards by gallery-girl avatars. Acid-wash bitching and kookaburra laughter plays mise-en-scène to this tequila-swilling, character-driven critique of the multimillion-dollar art world in loop-de-loops of ambition and a slow, masterful cancellation of power.

The story pivots—occasionally—around the unconsummated repartee of nymph Mathilde de Saint-Evans and her sororal sidekick Gretchen Salt. Orthogonal psychoanalysis of their sometimes-withholding lovers is projected and dissected under demi lune. Business as usual. Ambitious Mathilde—herself a kind of palindrome—works at an auction house in New York, the outcast in a lineup of scissored art world paper dolls and their jealous Baldessari-inspired blotting out. A gangplank walk led by Greenwich Village jockettes with uneven Maybelline eyeliner and Vaseline eyelids, living somewhere between art school intern and serial honey-trap wife. A psychodrama with a very particular pacing across New York, Paris, Munich, and Berlin under the neon lights of art commerce and motel twin beds you just know will be pushed together. Lucky Mathilde’s sidekick has got her back—occasionally.

Staking Mathilde’s perimeter in psycho-motor agitation is BFF Gretchen Salt, a black belt in small talk and speed-reading philosophy major on a first-name basis with Gilles Deleuze. Salt’s the hectic friend who talks like what she’s got to say is too urgent for punctuation (it never is), a girl who’s been given everything and still manages to fuck it up. She’s terrific. Through insupportable nervous troubles, Mathilde and Gretchen’s friendship blooms on one side, amigas kvetching their crummy existence in kickass banter and legit (maybe) ADD. A monozygotic pursuit of the pleasure principle vis-à-vis Klonopin or uppers or casked Midori.

Beyond the holy grounds of art world gossip, dirty Jacuzzis, money-bought art careers, and desire (hella unhinged), The Superrationals is something quite exquisitely painful: an elegy to a dead mother. Mathilde’s departed goddess-mother Olympia, with her celestial enchanté, sapphires, and lime bitters—a lady of the flowers, of the glass conservatory, a she-dandy in Louboutin editing Penguin Nietzsche with a nipple hanging out. A Delacroix-esque libertarian leading the people to a mirage, all without a hair out of place. While incorrectly performing freedom, Olympia amplifies and buckles memory—moored or unmoored, you can never quite tell. She is, of all things, an incorporeal reminder of the power of what is absent.

If there’s a libido at work here, it’s the pleasure and pain of uncertainty.

In fizzles and false starts from Berlin to New York, I chat with Stephanie LaCava, chaperoned by Tor, but more likely Mark Zuckerberg.

ESTELLE HOY: What a coup. The Superrationals is pretty much a self-induced aneurysm and my newfound amulet. The meta meaning—it’s hyper-aware of the world and anything but neutral. Non?

STEPHANIE LACAVA: So aware that one of its narrators is told by his lover and editor that he’s “too self-aware, too present. I want to forget you’re the writer.” This message is recounted on the page, first delivered on a room service menu slipped under his hotel room door. It’s a very disorienting book in that its staged aloofness and unfeeling somehow stokes sensitivity in the reader. I had one reader tell me it gave her too much anxiety, which is interesting because on the surface it’s a cool narrative. Another wrote to me, “I have no idea what to do with this book.”

EH: It seems like time is perversely multiplied or negated in the book, the way you poker-shuffle the narrators and cities and even style, as when you interrupt the narrative with excerpts from Mathilde’s earnest, deliberately unconvincing thesis. It’s reminiscent of Jean-Jacques Schul’s cult classic Dusty Pink [1972] with these dazzling cut-ups and portraits, even pharmaceutical leaflets. It achieves a fantastic disorientation. Is that the experience you wanted for the reader? Why?

SLC: You know those lame inspirational memes, like, “Life doesn’t happen in a straight line, it’s more like an infinity loop,” or whatever. You shuffle tarot cards for elucidation, clarity. Every kind of psychic or magical medium involves chance led by unseen forces. A Ouija board wrote one of The Girls chapters (not really). I love Schul. I interviewed him once at his home. I also admire how he doesn’t really feel the need to have a constant output. My book is musical in its own way. The ideal would be like a jazz song with elusive harmonies.

EH: Yeah, it kind of accelerates and accelerates, dreaming it becomes reversibility. The reader physically assumes the cadence of the text. “If I paused too long, I’d be paralyzed,” Mathilde says. It really speaks to the attention economy in the art world. There’s this wildly funny scene where some artist heavyweight dies and the girls from the New York office immediately discuss “tactful” ways to email their clients so they can buy up before The Times runs the obituary. Tongue-in-cheek passages like this are less a mirror to life, and more a revolutionary overthrow to tell people how to live—or at the very least, pay attention and make some cash from it! Can you tell us a little about how the book speaks to the attention economy of the art world?

SLC: I have a personal story in which someone who was supposedly the epitome of decorum and taste—whatever that means—didn’t send someone who worked for them a wedding gift, but always sent the most incredible presents to people on their “A List.” What kind of bullshit is that? Exactly the kind that comes with an attention economy. I mean, a wedding gift is a bad example, but it is to simply say that in whatever world where “etiquette” is paramount one would think this would apply to everyone, not just whomever is optically desirable. Meanwhile the person who was consciously—or worse, unconsciously—overlooked for the simple symbolic gesture had devoted her life to making his easier. Gross. I suppose I digress, but it’s the same thing to tactfully discuss how to make a profit off of disaster. We live in a world of in-between where the outward facing is prioritized like creeping disease. I think humor is a good way to attack this.

EH: Chris Kraus mentioned the book’s place in the jeune fille genre, where the truth behind the cliché is revealed. Michèle Bernstein’s All The King’s Horses [1960] comes to mind. Beyond turtlenecks and an ironic lampooning of the art world, the book appears to stretch the genre to the edges with a fiercer inclusion of psychoanalytic material, young-girl rage, and revenge. Can you speak a little to that?

SLC: Mathilde is shaped by trying to figure out the trauma of having been left alone in hotel rooms while her mother met her lover, and of having her mother offer no elucidation about goodness or humanity (the scene with the incorruptible). Everyone cares about her because of what she can do for them and not what she thinks, certainly not what she feels. She’s ostensibly an orphan with no friends—we can get to Gretchen later—an absent husband, and a legacy that haunts her. Of course Mathilde wants revenge, but her revenge is pathetic. Then again, so is her world. She feels really powerless, and art doesn’t feel powerful to her in its object form. Maybe she’s mad because she’s missing nuance, but how often in real life do things actually get really out of control and veer into the cliché. All the time.

EH: At your reading at After 8 Books in Paris, you mentioned the wild coincidence of discovering the book’s cover image: Hervé Guilbert’s photograph of a woman at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris wearing a black ribbon in her hair [Isabelle Adjani, Jardin des Plantes, Paris (1980)]. This is an exact scene in the book, yet you discovered the image after the work was written! Later you mentioned a cool reverence for something Ottessa Moshfegh said in an interview with The Guardian, something like, “Yeah, I’m trying to game the best seller.” Now I’m hoping the ribbon story is a story to sell a story. Some salable myth you fabricated. That would really push the jeune fille genre to the extreme.

SLC: I wish I was that clever. It’s a true story. Perhaps the only one in the book. I have the email I sent to someone in total shock when I found the photo months after the manuscript was complete.

EH: How does Olympia fit in to all of this? To my mind she’s a sign that absence is not what depletes and saps the system of representation, but rather makes it possible. And maybe a signifier of the cognitive dissonance in memory. She’s retold lovingly by Mathilde as this decorative hotshot editrix, a tuxedo-wearing, avant-garde, pen-in-hand-twelve-hours-after-giving-birth type. But then she says things to Mathilde along the lines of “I made you and I’ll destroy you.” It’s like, you know that iteration happened, but maybe not as described—a dueling recollection that tears memory apart, yet without causing fissures. This two-plane semiosis has a viselike grip throughout the book. Can you give us an analysis of this?

SLC: To put it simply: fantasy or erotic love works best by never being arrived at. Tell a lover a relationship is impossible, and you are the beloved forever. Not a new thought. One of the oldest. Triangulate a relationship and the one on the outside is the true love, cycles back to her/him, and the other becomes the desired. Olympia is named for the robotic doll in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman [1816]. Robert never gets to be with her in a real way because she dies. This assures they will never reach relationship stasis. Every memory becomes clearer and more desirable as he ages, alongside her memory. Olympia is no longer Olympia. In fact, she never was. Total fantasy.

EH: I love slippages in language. I asked a man on the streets of Paris to direct me to the Jeu de Paume [the contemporary art institution, but the term also means a game of tennis] and he took me to the Carrefour supermarché for some jus de pomme [apple juice]. He thought I was diabetic. You have a Saussurean penchant for linguistic slippage, too. That moment Olympia’s house help tells her “I crimson your books,” she means I read your books. Such a hoot. What’s your motivation behind the word games and phantom palindromes? How does this semiotic activity conspire with the jeune fille genre?

SLC: Wordplay is everything to me. When it lands, it touches on the unconscious and connection. It also makes sure no one is ever completely understood. G-d forbid two writers are texting each other. Massive problems ensue. I think English-as-a-second-language slipups are extremely charming and indicative of this same impossibility of communication. I just had a French friend tell me we needed to “brainwash together.” She meant “brainstorm.”

EH: [laughter] There’s this weird dissociative concussion that comes from reconciling a critique of the sexist, transactional art world that’s artistically achieved by embracing cliché representations of women. Are you concerned that people will misread the book?

SLC: For sure. One critic told me straight-up it was incredibly un-PC. But isn’t that what that 2015 world was? I didn’t write this story to prove my own morality; I wrote it to make myself uncomfortable. And other people uncomfortable, too. It can be read in endless ways. You can even read it as a drinking game. Open a page and whenever you get a certain affect or word, take a shot. Whatever you want. It’s just a book.

EH: I know coincidence is almost a religion to you, so I should tell you that after I read your book in preparation for this critique, I wrote the line: “Perhaps we should start at the center of the story.” I found out that night that you wrote the book by starting in the middle! I might be a convert.

SLC: [laughing] Is that story a story to sell an interview?

EH: I’m low-key wondering that myself.

Stephanie LaCava is a writer based in New York. Her work has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Artforum, Texte zur Kunst, the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, Vogue, and Interview.

Estelle Hoy is a writer and critic based in Berlin. Her second book, Pisti 80 Rue de Belleville (After 8 Books, 2020) was just released, with an introduction by Chris Kraus. Her forthcoming, Midsommer, cowritten with Sabrina Tarasoff, is scheduled for release with Mousse Publishing in spring 2021, with an introduction by Quinn Latimer and Anna Gritz.

Reynaldo Rivera’s Photographs of a Los Angeles That No Longer Exists

This article originally appeared in Hyperallergic, published on December 15th 2020, written by Chris Kraus. You can find the original article here

Below is an excerpt of the essay “Some Provisional Notes Toward a Disappeared City” which appears in Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City, edited by Hedi El Kholti and Lauren Mackler, published by Semiotext(e).

Como Buena Mexicana sufriré el dolor tranquila

Reynaldo Rivera started taking photos of people around the hotel — not his dad or his friends, but of the women who cleaned. He asked an elderly woman named Minnie to pose like a star in an old silent movie. The results made him want to do more. In these early photos, the dull, rundown, and depressing St. Leo Hotel and the grandmotherly lady who called him lil chicken were transformed into something bigger and better than life. Photography was clearly the next best thing to making a movie. He dropped his rolls at a downtown Photomat; most of the prints came back blank. When he asked the girl working there what he’d done wrong she told him about f-stops and focusing. He was thrilled when he finally began getting images back. He worked the cannery job for four months each summer. The rest of the time, he lived in LA. He left the cholo and gang world behind him and didn’t look back. In Stockton, he played old records by Edith Piaf, Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, and Louis Jordan on an old victrola he’d found in a secondhand store. And he followed new bands. In LA, he went to clubs, bleached out his hair, and wore vintage clothes. He reconnected with his cousin Trizia, who was “the most beautiful and cool girl I’d ever seen.” Through Trizia, he met the photographer Michael Rush, a veteran of the 1960s London underground scene. Michael taught him more about photography, and they both introduced him to cocaine.

Reynaldo Rivera, “Gaby, La Plaza” (1993)

There was a lot of cocaine, and eventually things would blow up. But in the early ’80s, Trizia and Michael were his gateway to another world. Through them he met Myriam Sorigue and Alex Jordanov, a French couple living in Hollywood. Alex Jordanov worked for Celluloid Records and started Radio Club, the first rap club in LA. Myriam liked Rivera’s work. Myriam set him up with his first photography job, taking photos for Ice-T’s girlfriend. He bought a new Pentax K1000 camera, and took the 1983 black and white glamour photos of fresh, pixieish 19-year-old Herminia in the hallway of an old rooming house, in an alley behind industrial buildings downtown. “In LA, I started documenting everything around me. It was my way of being able to hold onto things. Moments that ordinarily would have disappeared, I would take home to relive over and over. It was some kind of insanity. Because photography was always so expensive, I really had to be careful about how I used my film, because I had no money when I wasn’t working in the cannery. I shot a roll here, a roll there.”

Reynaldo Rivera, “Ramona Ortega and Gia Hernandez, Dreams” (1995)

Rivera lost almost all of his earliest work in 1985. By then, Michael and Trizia’s lives had taken a much darker turn, with their drug habits out of control. They were sharing a house. Once, in a rage, Trizia locked him out and when he came back to retrieve his things, most of his negatives were no longer there. He still has the photographs he took in Mexico City in 1983, of the room in Tepito where his step-grandfather was killed. At that time, Tepito was still an underclass neighborhood known for its open-air markets of counterfeit and stolen goods. Rivera and his father had traveled there, weeks after the murder, to help his grandmother deal with property matters. She and her late husband had owned the semi-communal slum building where the murder occurred. “In Mexico, buildings like this are called vecindades — I don’t know where this word comes from. They have courtyards in the middle, called patios, and the deeper inside the vecindad, the poorer you were. There was a song, very popular in Mexico in the ’40s, called Quinto Patio (Fifth Patio). My grandfather was killed by a man with a machete, the boyfriend of someone who lived there. This lady was getting beaten. He went to help her, and the guy just chopped him up. So I went in the room, with my dad, to check the place out. And I took photos of all the blood splattered everywhere. There was a big, framed saint on top of a table, splattered with blood. It was such a creepy image. My step-grandfather was such a nice man, the only one that showed us any kindness. We really felt his departure. That was the first time I went to Mexico City as an adult.” The photos Rivera took in that room are anomalous to the rest of his work. They are a literal document of a horrific and filthy crime scene gone stale. Images of landscape and streets produced in subsequent trips are emotionally rich triggers of portent and imminence. In a photograph taken while traveling in Central America, a passenger boat moves through an empty, dark lake under a cloud-leaden sky, and the bland windowless hall in “Bus Stop, Mexico” (1991) feels thick with echoes and ghosts.

Reynaldo Rivera, “Crime Scene (step-grandfather), Mexico City” (1983)

Across his body of work, Rivera depicts people enmeshed in their own private worlds who completely transcend their surroundings through the force of imagination and their inner lives. This remains true, whether the subject is photographed in a garden, a public toilet, or a house party in pre-gentrified Echo Park.

Reynaldo Rivera, “Girls, El Conquistador” (1997)

Reynaldo Rivera, “Montenegro, Silverlake Lounge” (1995)

I think this is a primary difference between Rivera’s work and Nan Goldin’s, to whom his portraits of drag queens, trans women, and other friends might be compared. Goldin’s subjects in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency are downwardly mobile: middle class kids who took a wrong turn, captured in louche dens of bohemian squalor during emotionally intimate scenes. Her color-drenched portraits of drag queens taken five years later in The Other Side are deliberately realistic. Jimmy Paulette’s face looks like a death mask in “Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC” (1991). His makeup is overdone, his fishnet midi is ripped, and the two of them look like pissed off punk girls confronting the sun after a long debauched night.

Reynaldo Rivera, “Paquita, Le Bar” (1997)

Rivera’s photographs of drag performers taken in Latino gay bars in LA between 1989 and 1997 reflect a different kind of collaboration. He sees his subjects less as they “are” than how they most wish to be seen, lending himself to their dreams and illusions of glamour. And why shouldn’t these dreams be realized? Wearing a blonde wig and a long taffeta wedding-cake dress, Yoshi floats off the dirty linoleum of the Mugy’s stage “(Yoshi (owner), Mugy’s,” 1995). Wrapped in a towel and a turban, Tina stands on an old wooden chair with a dollar tip tucked under a bra strap, but she’s in heaven. Her eyes closed, the pale shadow rests on her lids and her head tilts gently back as she moves to the music. She’s so forcefully channeling fragile delight that you have to look twice before seeing her masculine triceps and shoulders (“Tina, Mugy’s,” 1995).

Reynaldo Rivera, “Elyse Regehr and Javier Orosco, Downtown LA” (1989)

By the time he was 19, Rivera stopped going to Stockton for seasonal work. A musician friend introduced him to friends at the LA Weekly. He got a job as a janitor, where he stayed for about a year. Being involved with the paper gave him access to concerts and fashion shows. He took pictures at these events for his own pleasure, and later on sold his prints to the Weekly. Between 1985 and 1990, he photographed dozens of artists and bands, including Chaka Khan, Nick Cave, Sade, Vaginal Davis, Bob Dylan, Siouxsie Sioux, Echo and the Bunnymen, Depeche Mode, Tom Petty, Ray Charles, and many others. None of these shoots were assignments. “I got to choose the people I wanted, and I would photograph them however I wanted to. Because for me, they were the same as my other photographs. I was doing the work for myself. Except for the concert photos, I usually took the photos at their homes, or in other scenarios that were interesting. There’d be times when I got to spend the whole evening hanging out. The pictures of Siouxsie, we took at her birthday party. I remember people saying they didn’t look like photos they saw from regular shoots. They looked like art photos, as opposed to commercial photography. Maybe it’s because I wasn’t thinking, oh, I’m doing this for my career, to put on my resume, so I can sell it — I’m doing this for myself. Photography, for me, was that space between reality and make believe. It kept me protected.”

Reynaldo Rivera, “Vaginal Davis, Downtown” (1993)

His friend Gloria Ohland, then an editor at the LA Weekly, brought him along to fashion shows by designers like Christian Lacroix, which he photographed onstage and off. Although most of the negatives for these photos have been lost, I imagine them as precursors to the pictures Rivera would take several years later, an enormous body of work, of performers in Los Angeles drag clubs.

Reynaldo Rivera, “Siouxsie Sioux, birthday party, Hollywood” (1986)

The concert photos he took during those years are remarkable for the relations that they reveal between performers, and the act of performance itself. They provide psychological insight into the dynamics at work among band members. His photographs of Eurythmics performing in 1985 at the Whiskey feature Annie Lennox scowling, seducing, and exhorting the audience, supported by an energy field running between her and guitarist Dave Stewart that feels almost visible. His photographs of Depeche Mode’s 1988 concert emphasize the carefully measured moves of lead singer Dave Gahan’s performance. Photographing Chaka Khan’s show at the Wilshire Bell a year later, Rivera turns from the stage and considers the audience at this small venue, completely connected to the performance, almost as one.

Reynaldo Rivera, “Sonic Youth at Anti-Club, Hollywood” (1985)

Rivera’s approach to producing these concert photographs wasn’t exactly a matter of framing, exposure or angle. “At the end of the day, it’s how you picture the world. And this is where one photographer is different from another. At the concerts, it would be about finding that moment — the way I want them to look. Sometimes, out of 200 frames, you get two really good ones. Sometimes I didn’t get anything. But if you look at my band photos, I think you’ll see I made the effort to give them more depth. To make it a multi-dimensional image, as opposed to a flat concert photo. I’ve never been into this. I needed them to say something, if that makes any sense. I always look for the image to speak for itself. Whoever looks at the photo, it’s going to say something. My photos are very documentative, laying testament to things that happened. But at the same time, it’s about creating a narrative, a movie. And I see the people as characters. You can say this about all of my work. Sometimes I ask myself why I spent so much money, which at that time was so scarce, on photography. I was constantly creating the movie I wanted to be in, as opposed to the one I was born into.”

Reynaldo Rivera, “Cindy Gomez, Echo Park” (1992)

The photographs sold to the LA Weekly comprise just a small part of Rivera’s body of work. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, he continued taking pictures of parties and people around him. He traveled to Mexico, Berlin, and Central America, sometimes staying for months. Photography was that space between reality and make believe … The photos he took during these travels often loop back to his literal childhood, as well as his childhood fabulations and dreams. The slick surfaces and glowing street-lights during and after a summer monsoon in Mexico City recall the Paris streets seen by Brassaï, Germaine Krull, and Ilse Bing. The gestures, hairstyle and dress of a bolero performer seen in the street evoke the glamour of Mexican film stars of the golden era, but triply filtered through the passage of a half-century, poverty and old age. A tenement courtyard evokes the Tepito vecindade where his grandfather was murdered; a boy on a metal chair gazing into the camera could have been him two decades before. His photographs of indigenous children selling things in the street could have been ripped from an old National Geographic magazine or The Family of Man; they belong to another world. Later, he travels south to Chiapas and Guatemala. He stops at the edge of a village where a traveling show has set up an old Ferris wheel. The place feels as lost and remote as San Diego de la Unión seemed when he was a child.

Reynaldo Rivera, self-portrait, “Echo Park” (1996)

“The photos were part of something I was documenting. And so all my work looks — if you put it back to back, it doesn’t matter what the subject is, it’s like one big movie. Whether I was taking photos at fashion shoots, concerts, at home or the clubs in LA. They are all of the same kind of atmosphere. Usually dark.”

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s ”the freezer door” On Bookworm |KCRW

Author, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore | Photo by Jesse Mann

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, a transgender writer, speaks about crafting a narrative from the inside, internally, rather than imposing it. Her new book “The Freezer Door” explores the idea of radical visions not predicated on dominant norms, and the challenge of finding these visions in the gentrified gaze of contemporary cities. She discusses disappearing into books and her vulnerability, searching for connection with the world and people and the text itself, and writing what she’s most afraid to write in order to go on living.

Rude Pieties: Six Glimpse of Hervé Guibert

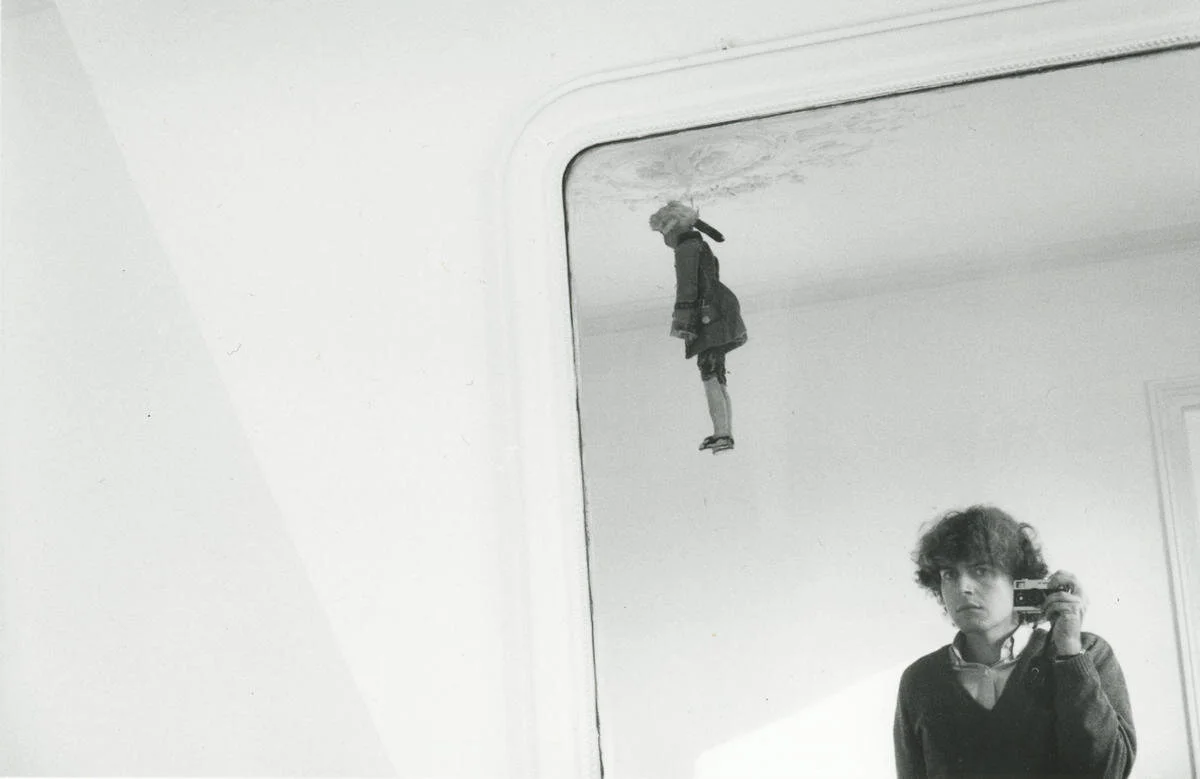

Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait, 1981. Courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts

Rude Pieties:Six Glimpses of Hervé Guibert

Moyra Davey, Lia Gangitano, Bruce Hainley, Hedi El Kholti,

Wayne Koestenbaum, Christine Pichini, Janique Vigier

Published in Bidoun December 2020 The original article can be found here

We have no list — not in his letters, not in his voluminous diaries, nor in his various books of autofiction — of Hervé Guibert’s formative memories, those that might make up the carousel in a slideshow of his life. But from the texts and photographs, we can imagine:

• The tangle of his great aunt Louise’s hair, sprung out from her thick braids at the day’s end

• His father returning home at night from the slaughterhouse, his apron bloodied

• His mother’s carefully made up face

• His lover Thierry’s ass

• The white woolen garment he could never let go of as a child

• A menagerie of ceramic horses, marbles, marionettes, figurines

The French writer, artist, and polymath lived his thirty-six years with propulsive force. To this his work bears witness. He published seventeen novels in fourteen years; he was the long-standing photography critic for Le Monde; he penned trenchant correspondences and caustic love letters. He photographed friends and lovers, dioramas and details of paintings, himself in shadow, a delicate compendium of palm-size objects. He made a single video, La pudeur ou l’impudeur (Modesty, or Immodesty), in which he recorded his final year with the bravery of someone who understands time’s violence.

Guibert was born in Saint-Cloud in 1955, the child of an aspiring bourgeois family that would inspire his disdain throughout his life. He turned his back on his domineering father, a butcher; he recoiled at his mother’s primness. Contempt often serving as a guise for fascination, the three existed in a psychosexual vortex around which his adolescent life orbited. At seventeen, he moved to Paris, where his cool beauty and careful aesthetic eye quickly granted him access to the leading intellectuals of the time. He was Foucault’s favorite; Barthes pined for him.

Guibert wrote constantly: in his diaries (now collected as The Mausoleum of Lovers: Journals 1976–1991), for Le Mondeand for the literature review Minuit, as well as stories and novels which flit between memoir and phantasmagoria, tracing impulse and desire with surgical precision. Ghost Image, his 1981 tract on photography, ranks alongside Susan Sontag’s On Photography and Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida.

His photographs? Hesitations, pulses, solitude, tenderness. He photographed to obscure the glint of death at the corner of his eye. The slim photo-roman Suzanne and Louise stages his beloved great-aunts in cadaver like poses, documents the arcane objects to which they devoted their lives; other collections take up the vibrancy of the body, to which he attended with a grace that recalls Simone Weil’s definition of prayer: “absolutely unmixed attention.”

He is often accused of having sold off his secrets, as if people haven’t met a writer before. His 1988 AIDS diagnosis only propelled him to work at greater speed. He gained national recognition and notoriety with the 1990 publication of À l’ami qui ne m’a pas sauvé la vie (To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life), a novel-cum-roman à clef that depicts with an unflinching eye the fear and mania of the AIDS crisis via a group of friends in France. The thinly veiled character Muzil, a famous author dying of HIV, was easily recognized as a stand-in for Michel Foucault, who had not disclosed his diagnosis prior to his death in 1984. The novel was read as treason, a ploy for stardom at the expense of friendship. But secrets do not necessarily violate the private life of the heart.

“I empty myself slowly,” wrote Guibert, early on in Mausoleum. “I exploit myself.” If this were his ethos, its ultimate permutation came with Modesty, or Immodesty, a video diary he recorded between June 1990 and March 1991. He vowed that “everything that could enter into the field of experience… could became a potential episode in the film.” “Everything” would come to encompass the banal and the sublime: medical appointments, a medley of drugs, conversations with Suzanne and Louise, sunlight in Elba, a staged suicide attempt, the persistence of life in death.

He died in 1991 of complications from an unsuccessful suicide attempt. A week later, the video aired on French television.

A possible epitaph? Better to remain hungry than to renounce appetite.

On the occasion of the republication of the English translation of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, the editors of Bidoun and Semiotext(e) invited six artists and writers — Moyra Davey, Lia Gangitano, Bruce Hainley, Hedi El Khoti, Wayne Koestenbaum, and Christine Pichini — to reflect on Guibert’s life, work, and ongoing resonance through his photographs.

–Janique Vigier

The Tingling Interregnum

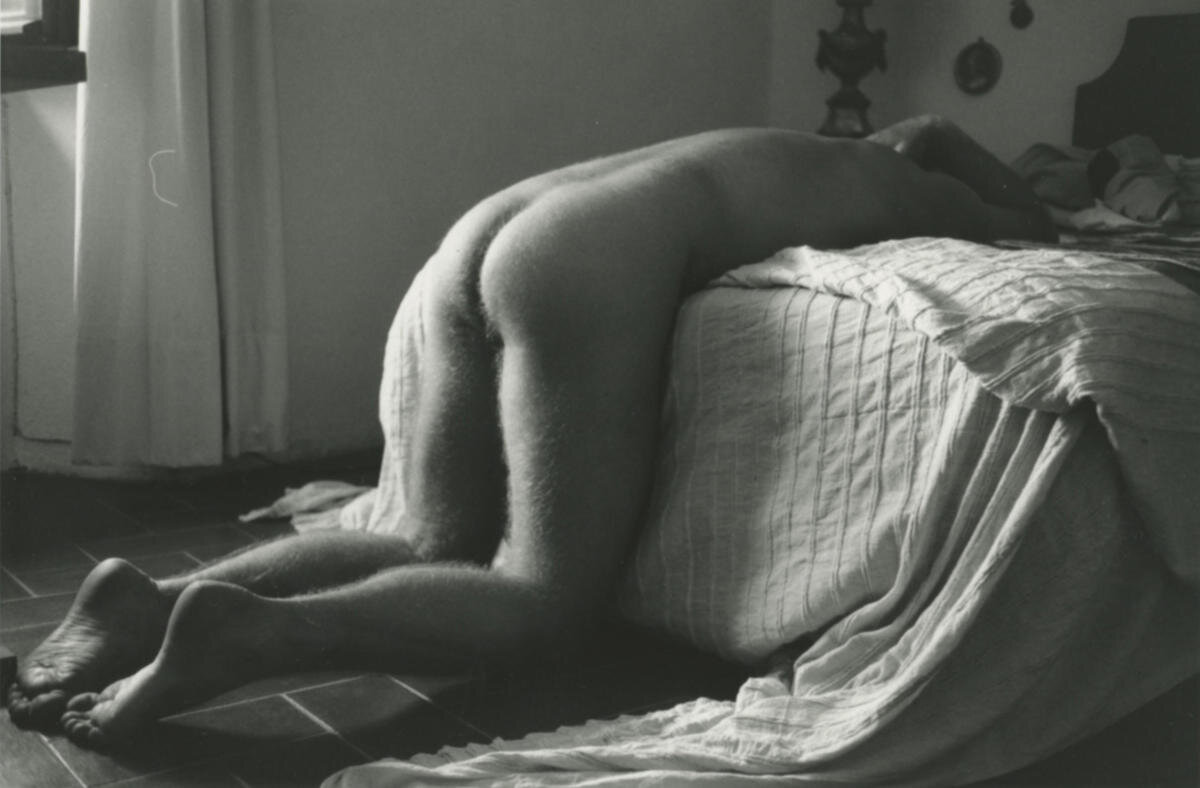

Facedown on the bed the naked lover lies. The ass itself is not in question. At stake here is the lover’s effacement, the drapes, the dim light, the soles of his feet, the dreary tiled floor, the convent mood, and the black and white film’s wish to evade contrast and, instead, muffle its aggressions in a swaddling envelope of grey. The man lying down is Hans Georg Berger, a fellow photographer, a close collaborator. The reason that Hervé Guibert bothered to become an artist and a writer was to find a formula for intimacies, to turn photographed or described intimacy into a nearly psychedelic tincture dropped in the water glass of the daily. To avoid recording intimacies — however rude and potentially obscene these closeups, however in danger of being stigmatized as narcissistic or masturbatory are these exercises in mortifying the body parts of every beloved — would have been a recipe for paralysis. If Guibert had decided not to make a life’s work of photographing his intimate acts and his own body and the bodies of his aunts and lovers, if Guibert had decided to stop photographing cocks and asses because that subject matter is tacky, it is a crutch, it has no philosophy behind it, it is irresponsible, it is as time-wasting as philately or numismatics — if he had ignored Berger’s bucolic ass and photographed a riot or a ruin, then Guibert would have stunk, in that moment when he faced, posthumously, his Maker; Guibert would have smelled foul to his Maker, who would have rebuked Guibert for ignoring his calling and responding instead to faux-moral strictures that call ass photography a putrid performance, as false and glossy as a ceramic crabapple. I’ll revoke your death sentence, Hervé, his Maker might have said; I’ll send you back toEarth if you promise to photograph every erotic and abject moment of your life and death, every pincushion, every pustule, every taint, every crack, every horizontality that includes a lover’s body waiting for your embrace. Hervé was reluctant to return to Earth, but he didn’t want to displease his Maker, who was kind enough to understand the importance of pursuing the ass and pursuing the ineffable thisness of what actually happens to you and what actually turns you on — even if what turns you on also bores you, even if you would now rather kibbitz about tonight’s rainfall than go to La Coupole to find the accidental trick who will read you Balzac and remind you that you have betrayed your parents. Parentage, lineage, pedigree, entitlement, legacy — now that you are back on Earth for a second visit to the bedroom where Hans Georg Berger once lay facedown on the bed to give his ass to your camera, none of the signposts of having a name — of bearing an identity — matter. Is it ill-mannered of me to remind you that Guibert never got a chance to return to Earth? His Maker was not hearing appeals the day that Hervé knocked. Be grateful that Hervé photographed the ass, even if the ass doesn’t come equipped with language to defend its right to uphold its own puny law, the law of simply being there, being available, being a token of receptivity, vulnerability, steadfastness, and a state of equipoise between hardness and softness that makes the logician in me start fidgeting because I’d promised to clamp down on vagueness and bring you goods that are measurable and everlasting. We are at our least communicative and our most universal when we allow our ass to face the camera, even if the commentary we supply later, postmortem, seems to cancel the bounty that our silence, lightly dusted with hair (itself a synonym for the ineluctable), had promised. I told you that the ass was not in question. Maybe I was wrong. The ass is “in question,” which is another way of saying that the ass is dwelling in a tingling interregnum; the ass is waiting to be proved worthy. You verify its worth by circling it with as much fuss and intricacy as possible. Make a big deal out of me, suggests the ass. Overload me with ore. This photograph and this paragraph are sites of overloading, places where portents cluster as if on piers or in parks. The ass is a thesaurus where rough equivalences gather to commiserate, where a noun rubs against a near noun. A word (ass is a word) makes sense only when a contiguous word demonstrates that similar objects (my ass, your ass) are not the same. Not being the same, but almost being the same, is what the Maker calls succulence. That’s why I can’t stop being shattered by nude images, their staggering obstreperousness, their insistence on being superior to the occasioning flesh. A pair of buttocks caused the photograph. Causal buttocks, preliminary and disposable. What remains is this cleft document.

–Wayne Koestenbaum

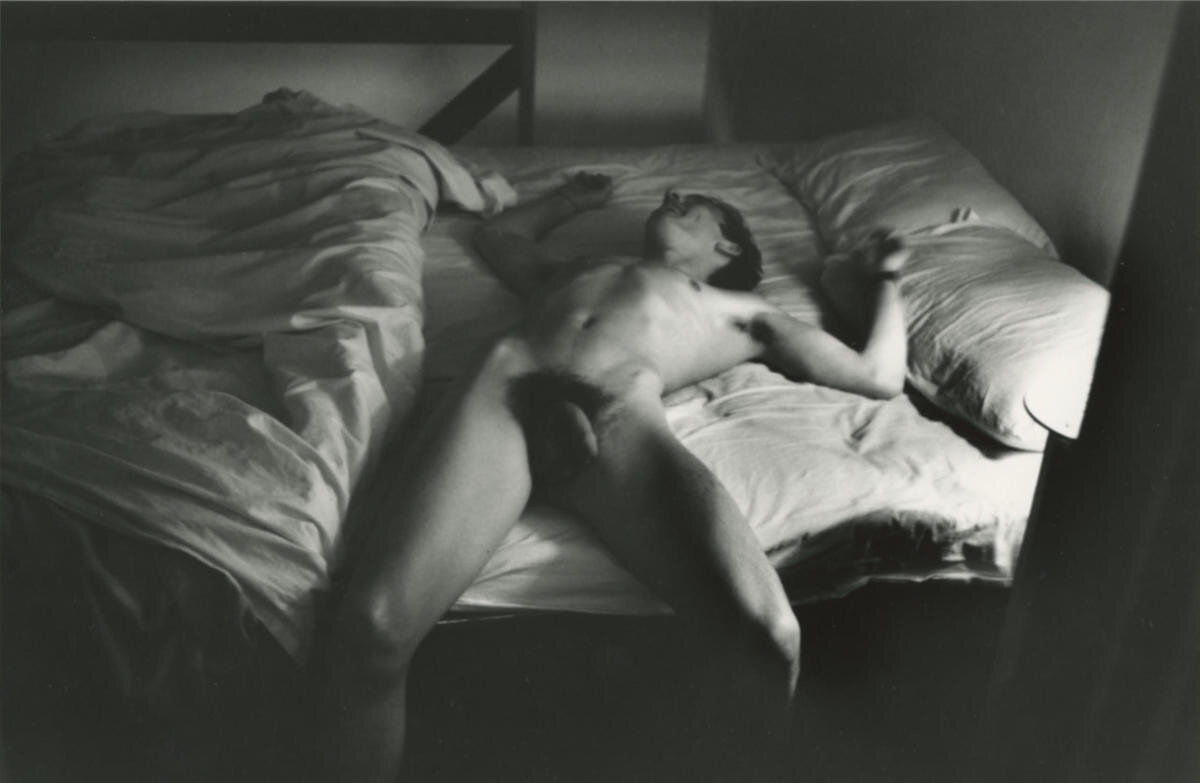

Hervé Guibert, Vincent Nu Couché Villa Medicis, 1988. Courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts

It’s tempting to quote him (HG), deadheading descriptive obbligato, “commentary,” my own voice (even more exhausting than the idea of commentary), to cherry-pick a few choice accounts from the journal about Vincent, whom Thierry, HG’s lover and the father of his wife’s children, called “a maggot and a shit” as well as a “glabrous gnome.”

I put both Le mausolée des amants and the translation of the journal by Nathanaël, The Mausoleum of Lovers, on my desk, but, even with my rusty French, I’m distracted by the word mausolée, with its terminal unaccented e making it look like it should be a feminine noun, though, preceded as it is by le, clearly isn’t. If I were Francis Ponge, I’d have a dog-eared Littré at hand to stroll along the etymological stream of the word to the source of why it came to be spelled the way it is; I’d find a malformed way to pun on the mausoleum’s mal soleil.

An online version of the Littré confirms the noun’s gender, derived from the Persian ruler Mausole, husband of Artemise, his sister, who had a magnifique tombeau raised in his honor. One of the seven wonders of the ancient world, revered not for its size but, until Christians demolished it, for its beauty, Mausole’s tomb soon lent, lends still, the interred satrap’s name, par extension, to every magnificent tomb, or “mausoleum” — which, whether or not wet with tears as in La Fontaine, the electronic Littré cautions shouldn’t be confused with “catafalque.”

Vincent Marmousez’s glans, his shaft, hopeful in the black plush of his thick bush, might strike some as this photograph’s raison d’être, but really, it’s his laughter. Teeth softly gleaming in his smiling open mouth prove his easy joy, ridiculousness a part of the entire erotic scenario. “Another picture? Of me?” I imagine him blurting out, before falling back onto the bed, laughing. Click.

HG loved this one, who called him darling — Last night, Vincent broke a glass against his forehead, insulted the servers of La Coupole, called me my darling, then in tears kneeled before me to kiss my glans — enough to kill him several times in various books, right at the start. Vincent came over to HG’s apartment to get stoned and fuck around — sometimes directly from his girlfriend’s, ready to party, pussy-fingered — or, since Vincent was often already stoned, to get stoned again and fuck some more. The last time he kills him in the journal, HG daydreams they’re in Martinique, wondering if it’s the start of another récit: Vincent éventré, l’abruti, sur la barrière de corail au large des Salines, je me retrouvai seul au bout de monde… (Vincent gutted, the bozo, on the coral reef off the Salines, I found myself alone at the end of the world…) A bad son under a bad sun. In Le paradis, HG’s last novel and my favorite, instead of calling Vincent a bozo, he has become Jayne (éventré shifted to éventrée) and is dubbed l’andouille, “the meathead.”

Why this picture now?

No death. Life in the midst of living. Someone being loved incandescently, knowing it, returning the love, not belittling it, with laughter, fleeting guarantor of truth. Before antiretrovirals became readily available. Long before deep-fried memes came to life.

Call it Once Is Not Enough — or, better, L’odeur des garçons, a title HG toyed with but never got around to using.

–Bruce Hainley

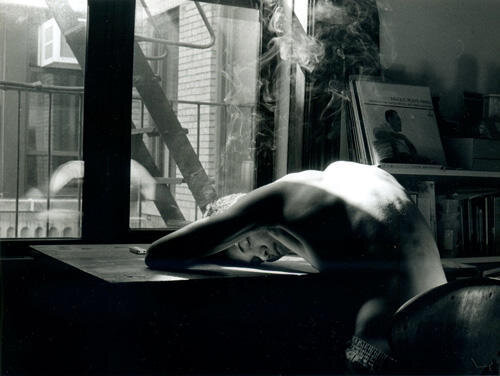

Hervé Guibert, Sienne, 1979. Courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts

I came to Hervé Guibert by way of friendship. First, it was the artist Heinz Peter Knes who introduced me to Guibert’s photographs, and soon after, another artist, Pradeep Dalal, loaned me Ghost Image, Guibert’s essays on photography, which I quickly read and felt compelled to write about.

I had been telling Heinz about Francesca Woodman and showing him her books, which he had never seen, and he said: I want to introduce you to someone whose images have something in common with Woodman’s, and whose work occupies a similarly high place in my personal pantheon of artists. He pulled up Guibert on a search engine, and I could immediately make out the affinity.

Straightaway recognizable: Parisian apartments with their high windows and paneled walls and doors with dangling keys, and the particularity of the light that characterizes these spaces. Compositionally, they’re more classical and controlled than Woodman’s experiments with performance, disintegration, and the blurring of motion. But both artists have much in common: an old-world sensibility, a focus on bodies and interior space, along with expertise and control of black and white registers. Both spent considerable time living and working in Italy, where each staged photographs in rooms of similar genteel decrepitude bathed in southern light.

Not all of Guibert’s work is polite. There are many full-blown erections occupying center stage. If one looks beyond the essays in Ghost Image,to the fiction and autofiction and the collected diaries titled The Mausoleum of Lovers, there is fucking and shitting and some of the most forthright and courageous writing on the themes of illness and dying I’ve ever come across.

It’s hard for me to choose a single favorite photograph or text by Guibert. In my conception of him, pictures and texts inform each other and are part of a whole with many different valences: classical, scatological, erotic, angry, hateful, narcissistic…

Barney Simon-Davey, Untitled (Eric, after Hervé Guibert), 2014

A certain image has been made singular, though, by my son, who decided to restage Sienne, 1979, some years ago for a school assignment, using his good friend, Eric, as a model. Sienne is marked by light streaming through a high window and catching in its beams heavy curls of smoke hovering just above a man’s prostrate torso. I helped my son determine when the light would be optimum for his reenactment, and then I left him and his friend alone. The resulting photograph is a notable tribute to Sienne. Unlike the mythic Italianness of the original,my son’s photo is decidedly new-world, with a New York fire escape clearly visible just beyond the window in the courtyard. And yet the men’s shoulder blades are similarly highlighted and sculpted by solar rays, as is the white, swirling smoke. There is a suggestion of melancholia in Guibert’s Sienne, whereas I perceive in the image of Eric an homage to intoxication and friendship.

–Moyra Davey

Hervé Guibert, Autoportrait, 1981. Courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts

First effects of Hervé Guibert’s Autoportrait, 1981: fascination, longing. An ache in the heart that travels along the crescent shadow parting his lips and aligns itself with the tilt of his jaw, a flutter of thrill at the glimpse of his face in the mirror. Guibert’s autoportrait flirts with his autofiction, that combustible genre which suspends real and unreal in search of a slippery “true.” I want to fathom his features, trace his curls. I want to look him right in the eyes, but our sight lines are ever so slightly askew.

Barthes writes that Avedon’s portraits of subjects who look us right in the eyes produce an “effect of truth,” that the gaze “acts as the very organ of truth.” But Autoportrait does something else. Shot in a (bathroom?) mirror, its trajectory of seeing toward being-seen and back again zigzags from Guibert’s eyes to the mirror to the camera’s lens. He shoots his reflection on a bias, a slant selfie from an invisible camera he holds in a hand just beyond the frame. If the studium is HG’s empirical beauty, the punctum is that kinked, ricocheting gaze. We hear the shot whizzing by, are wounded by its shards. And yet somehow it feels like a direct hit.

Seeking connection, I try to true the gaze, to place myself squarely in HG’s sights by drawing the photograph freehand. As if translating the image into a drawing could somehow consummate the act of seeing. Drawing as correspondence: a sort of séance or mystical conduit, the key to settling into the gaze’s groove. But every attempt to draw the photograph fails; the inky black eyebrows turn monolithic and severe, wrecking HG’s sublime face. I take a different tack — tracing — what I wanted to do in the first place; I trace his features with my fingertips, the photograph on a light box with small dashes, stitching together his face with pencil marks. I think about making a stop-motion-animation film out of these drawings, or maybe a shadow-puppet play starring Hervé and Isabelle Adjani, something about television appearances and AIDS rumors and betrayal, but while writing the dialogue, I draw a blank after “You’re breathtaking. / I know. / May I photograph you?”

–Christine Pichini

Hervé Guibert, Zouzou

She Spent So Many Hours Under the Sun Lamps

There is something unsettling in Hervé Guibert’s austere 1978 portrait of French actress, singer, and model Zouzou. Standing in front of a white backdrop and seen from behind, she’s wrapped in a large white bath towel with her head slightly bowed. Another white towel, wrinkled and laid out horizontally on the floor, sets up a contrast between the towels and the surrounding blackness. The photograph, beguiling as it is, is an ambiguous invitation to imagine what we can’t see.

In Dusty Pink (1972), Jean-Jacques Schuhl’s elegiac novel composed of the smoldering embers of the 1960s, Zouzou appears as an emblematic protagonist of that period. Schuhl selects four moments — or movements, as if his book were a musical score — to create Zouzou’s portrait. The first collages newspaper captions to stirring effect: “Zouzou (the thin, pale, distant, smirking dancer [‘she’s the one over there with a British flag miniskirt, the most mini one in all Paris, when she goes to London she stays with George Harrison,’ declared Pariscope] syncopating her words, zazou zoulou — sophisticated savage.”

Pre-’68, she is Zouzou la Twisteuse, the famous nightclubber and fashion model, Brian Jones’s girlfriend and, briefly, Yves Saint-Laurent’s favorite model. “She had an androgynous style, which, compounded with her taste for revolt, made her a very modern character. She corresponded to what I wanted to express with my first collection. Sadly, we had to stop our collaboration after a few attempts; the discipline needed by haute couture, the rigorous fittings, the respect for schedule, didn’t suit her rebellious disposition,” the designer was quoted as saying in Zouzou’s autobiography, Until Dawn. Zouzou’s distinctive style had been perfected with the help of the artist and illustrator Jean-Paul Goude, her art-school boyfriend. She once recalled, “He cuts my hair really short… proposes that I wear very pale pantyhose, close to my complexion… forbids me to suntan… he loves my androgynous side, and pushes me to wear men’s garments… even paints color stripes directly on a beige sweater.”

In the second movement, Schuhl writes a three-line poem distilling the essence of Zouzou’s face, the face Guibert hides: “‘her lower eyelashes (and rings beneath) as if sewn on,’ ‘her nose as if broken,’ ‘her mouth as if painted.’”

The third movement alludes to Zouzou’s second movie with Philippe Garrel, La Concentration, a claustrophobic allegory of the filmmaker’s psychic crisis around May ’68. Here is Schuhl: “Strings and clips connected to electrodes are attached to her wrists and ankles for ninety minutes (fragile and synthetic).” Elsewhere, Garrel describes the largely improvised film, shot over 72 hours without interruption, as an indictment of spectacle: “We see two actors — Jean Pierre Léaud and Zouzou — rigged out with microphones, and confined in an apartment split in two zones, a cold room and a hot room, which are both torture chambers. A bed is set between the two spaces, encircled by camera rails.”

Neither Guibert’s diary, The Mausoleum of Lovers, nor Zouzou’s autobiography mentions the session which produced the photograph, nor do they disclose any memories of their encounter. Yet Zouzou describes posing for Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton in great detail: “Avedon is calm, levelheaded, discreet,” she recalls. “He takes very few photos. At the end of the session, he tells me, ‘You’re like Ava Gardner, in the way in which you can turn in two seconds from monstrous to sublime. It’s rare and that’s what I love most about women’s physique.’ Newton loves screaming. He needs a victim, the assistant or the magazine editor. With me, he plays the seducer. He portrays me as a tough bitch, forbids me to smile, and erases any trace of romanticism.”

At age twenty-three, Hervé Guibert is hired as a cultural critic for Le Monde, where he writes mostly about photography. Despite his youth, the breadth of his knowledge of the history of the medium is impressive, as are the seriousness and acuity of his criticism, emphasizing aesthetic criteria that could well apply to his own artistic project. In his 1978 review of a Lee Friedlander exhibition, Guibert writes, “Nothing happens in most of the photos. Absence of action, absence of sensuality, and even absence of meaning, since Friedlander shoots faces and traffic signs from the back. ‘A young girl, who knows nothing about photography,’ said while looking at Friedlander photographs: ‘There’s nothing wrong. But they give me a feeling of death.’ Nothing wrong, indeed, under the appearance of banality. As much as the preceding generation of American photographers (Weston, Caponigro, Adams, Cunningham) glorified matter, Friedlander cools it down.”

The same year, reviewing a retrospective by André Kertész, Guibert describes the Hungarian-born photographer’s work as “a pivotal oeuvre in the history of photography, which turns its back on the pictorial and portraiture while paying attention to all the small gestures that patiently weave life. Kertész’s photographs aren’t weighted down by an aesthetic discourse. They aren’t cold — not even the ones that seem to prioritize style. These photos could have been taken by anyone: they are the photos of an ‘amateur’… Kertész has said: ‘I see what exists.’ This isn’t naivety. It takes imagination to see reality.”

What does Guibert hope to convey of his 1978 encounter with Zouzou? The towel and the pose bring to mind the climactic scene in Eric Rohmer’s 1972 Love in the Afternoon, Zouzou’s best-known film. As Chloe, the bohemian object of a married man’s desire, she is down on her luck and trying to rebuild her life. Stepping out of the shower one day, she invites her admirer to dry her off with a generic white towel, much like the one in Guibert’s photograph. From there, the film moves toward its unexpected end, with Chloe alone and the man reunited with his wife. The character of Chloe was based on conversations Rohmer had with the actress around an unrealized TV series, The Adventures of Zouzou. At Love in the Afternoon’s New York Film Festival premiere, Zouzou made a triumphal entrance accompanied by Robbie Robertson and Jack Nicholson. At the after-party at the Factory, Andy Warhol, who loved the film, asked if he could take her Polaroid. At the Carlyle Hotel, she was accosted by dozens of fans. Obsessed with the Zouzou of the film, the critic Vincent Canby allegedly counted the beauty marks on her back.

Maybe Guibert sensed Zouzou’s need to retreat, to turn her back on her own image, to hide her remarkable face from the spotlight. He grants her that wish — a moment of respite. In 1978, the year the photo was taken, Zouzou was in the throes of a full-blown heroin addiction. An incident recounted in her autobiography underlines her desire for anonymity. Unable to financially sustain her expensive drug habit, Zouzou and her boyfriend set out to rob a drug dealer. That night, one of her films happens to be playing on French television, and the dealer recognizes her. A mutual friend intervenes, and things are arranged without incident.

Later that year, she leaves France for St. Bart’s in the Caribbean for a self-imposed exile that will last seven years.

–Hedi El Kholti

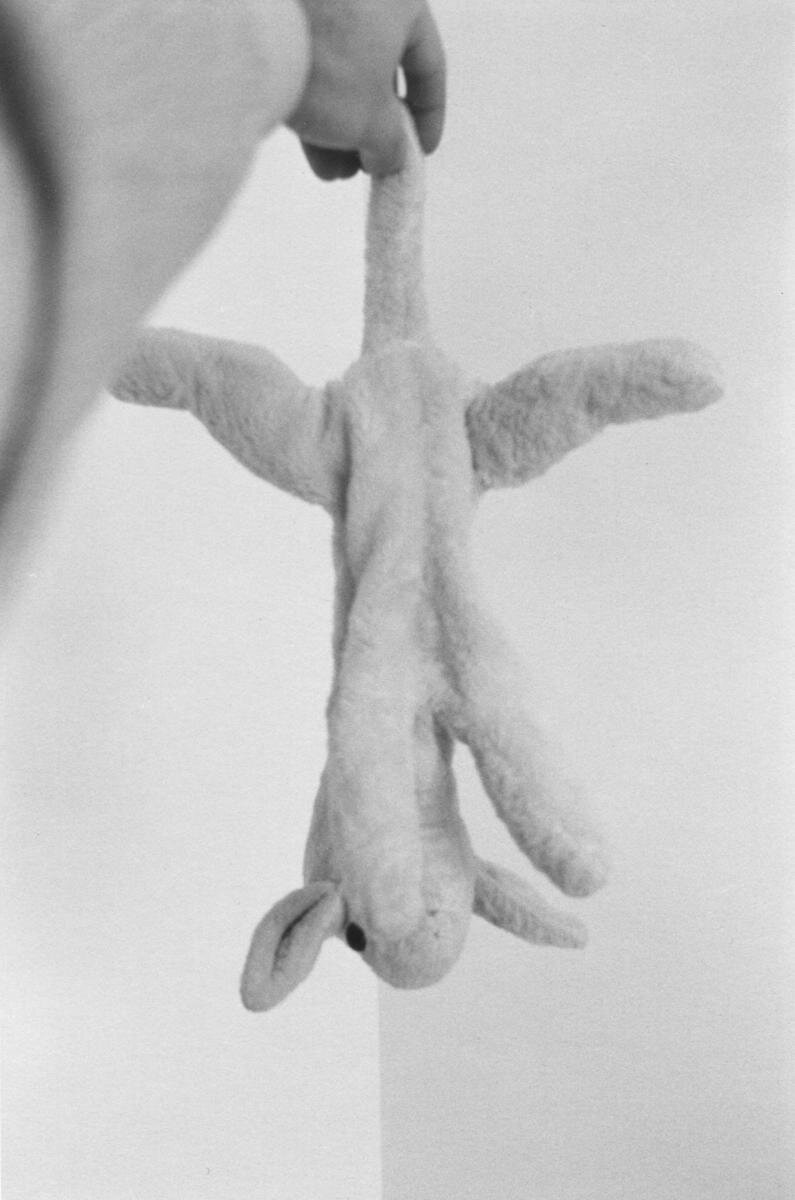

Hervé Guibert, Agneaudoux, 1981. Courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts

Agneaudoux

To understand photography as a way of representing what has died as wanting to be alive recasts the spectator’s wish for the return of the loved and lost or for the loved and lost to wish to return as the “want” of the photograph. It is also to reconceive the spectator’s encounter with the photograph as not a means of getting close to death but rather a kind of mad, even hallucinatory means of holding the cord of the fantasy of a returned love one never has to lose…

-Jill Casid, “Pyrographies: Photography and the good death”

Following the death of Ellen Cantor, my best friend — a term she reciprocated with “my future wife” in an epistolary work — I acquired a photograph by Hervé Guibert because it reminded me of her. It’s called Agneaudoux (1981) — loose translation, “sweet lamb,” and is probably a reference to the phrase “as gentle as a lamb.” I laughed — I laugh — because the irony of Guibert’s title also reminded me of her. Agneaudoux is a photograph of a small stuffed animal being held at arm’s length by the tail, its legs splayed and suspended upside down. Its charm is tinged with the permanent sadness of “wanting to be alive.” My friend’s work often involved imagining what it would be like if the “lifeless” characters of childhood grew up to have real adult lives. I liken Guibert’s stuffed animal to The Velveteen Rabbit, even if it’s a lamb — a little sacrificial, in the cinematic sense, its purpose being to die.

As affecting as I found seeing Guibert’s photographs in a gallery for the first time, my understanding of them is rooted in artist and theorist Jill Casid’s queer theory of “pyrography.” Her astounding essay “Pyrographies: Photography and the good death” is a close reading of Guibert’s photo-novel Suzanne and Louise through the writings of his friends — namely, Michel Foucault’s “The Social Triumph of the Sexual Will” and Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida and Mourning Diary. Casid teases out connections between photography’s unstable material qualities and its inextricable associations with mourning and death. By unwriting past-tense entanglements of loved ones and their pyres, she elegantly considers “what it means to use photography as a performative rehearsal for the catastrophe that has already happened.”

Casid posits the photography as the practice “of making volatile structures for feeling… in which one might begin to imagine and transact with care the losses and the letting go yet to come.” Throughout his life, Guibert was haunted by the specter of death. In a bid to draw it closer to him or push it away, he would experiment with it aesthetically: Suzanne and Louise is populated by staged simulacrums of his great-aunt’s deaths; at one point, he asked Barthes if he could photograph his ailing mother. In Casid’s discussion of these realized and unrealized works, impossible photographs that can’t or shouldn’t be made, she also speaks about love, mirrors, resequenced time, and the untimely. A note handwritten by Guibert that appears in the penultimate section of Suzanne and Louise reads, “A simulacra.” Here is Guibert’s photography as a “séance to the future.” I was told that if the kid in The Velveteen Rabbit loved his stuffed animal enough, it would become real. Maybe that’s why I like photography.

When my friend made an artwork from a photographed journal page describing me as her new mother and future wife, I felt the blush of exposure. She was omnilaterally in love with the world. It was a little embarrassing, this love. Thinking through the linkages between queer shame and narcissism, self-love and promiscuous affinities, in Eve Sedgwick’s Touching Feeling, Casid goes on to lovingly describe “the strange time-space of the photograph… as a kind of performance space and event, tantalizing with the promise of the narcissism of returned reflection and burning us with the shame of refusal. The queer stage or scene of the photographic contact [contract].”

In his love letter to his aunt Suzanne, Guibert writes, “When you feel yourself about to die, call me…” Like Guibert, my future wife photographed handwritten inscriptions and printed them in her published art books. Notes like “I hope you are well. Let’s be in touch soon” or “I miss you” appear on the back covers. What is given back, promised, and at times left unrequited is “transacted through the book or photograph.” Agneaudoux, like Guibert’s never-taken picture of Barthes’s mother, is unanswered love at its most resolute — a want, which is maybe just a failing to be alive. Or else a want that never dies.

For Ellen Cantor

–Lia Gangitano

What Abyss Are We Talking About?

by Franco “Bifo” Berardi

Published January 14th 2020 The original article can be found here

The essay published by Timothy Snyder in the New York Times Magazine on January 9 has a beautiful title, even if it is not very original.1 Reading the text, however, has been a little disappointing for me. Snyder writes:

Post-truth is pre-fascism, and Trump has been our post-truth president. When we give up on truth, we concede power to those with the wealth and charisma to create spectacle in its place. Without agreement about some basic facts, citizens cannot form the civil society that would allow them to defend themselves. If we lose the institutions that produce facts that are pertinent to us, then we tend to wallow in attractive abstractions and fictions. Post-truth wears away the rule of law and invites a regime of myth.

I obviously agree with this last point; that said, it explains nothing. What should be explained is why a large part of American society “believes” in systematically false statements.

By the by: does Snyder think that Trumpists “believe” in the words of Trump in a literal sense?